Closing the performance gap

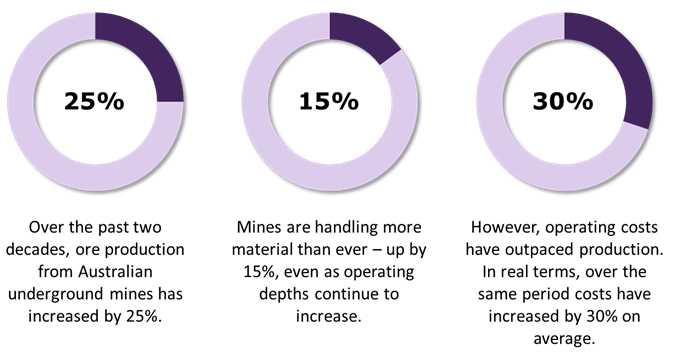

At the same time as production in the Australian mining industry is rising at an even faster rate, production costs are rising, leaving an ever-widening productivity gap. In a time of “turbulence” due to the spread of COVID-19, businesses are more than ever looking to strengthen profits and maintain profitability. The push for productivity can be seen both in board meetings focused on stock returns and in work teams trying to reduce risk and improve performance. At the same time, performance improvement is often confused with efficiency improvement, which usually negatively affects performance. However, the positive effect of such initiatives is unstable, as they do not systematically work. If performance improvement is not implemented directly through the mine plan, then it is often nothing more than a one-time measure that cannot be integrated into business processes.

Performance or Efficiency

Productivity is a measure of the ratio between inputs of production and output. A faster increase in the volume of inputs compared to an increase in the volume of output means a decrease in productivity. The increase in productivity occurs by increasing the efficiency of the use of initial resources. This is far from a new concept. This term is commonly used in the mining industry. But if the term is widely used, it does not mean that it is well understood. Perhaps the most common misconception in the industry is that efficiency gains are perceived to equate to productivity gains, but this is not always true.

The confusion between productivity and efficiency stems from the obsession with increasing output in the pursuit of maximizing economies of scale. Efficiency is a measure of the achievement of business goals, and companies should always strive to improve efficiency and productivity as a whole. Achieving business goals is an important element of success, but when it comes to productivity with a focus only on increasing capacity based on the volume of output, this is an illustration of the case when the cart is put before the horse. An additional hauler can help increase haulage, exceed targets, and increase efficiency, but if input growth outpaces output growth, you increase efficiency at the cost of reduced productivity.

Comparing 43 mines in AMC's Smart Data™ database over two different periods, it is clear that production has increased significantly. However, they were surpassed by a concomitant increase in operating costs. The mining industry is now producing more than ever, but mine productivity has not kept pace with efficiency.

Case Study

Let's look at a real industry example. One mine decided to improve productivity and efficiency through a strategy that focused on investment. Significant capital investments were made in tunneling operations at the mine: they began to be carried out in a larger volume and at an increased speed.

In the short term, the mine has achieved significant productivity and efficiency improvements. Ropulation efficiency (in meters) increased by 37% and maximum short-term productivity (in meters per day) increased by 33%. The business goals were achieved on time, and, naturally, the project was recognized as a success.

However, a few months later, at the end of the reporting budget period, productivity fell well below the original baseline, followed by efficiency, and operating costs became alarmingly high. What went wrong?

The first problem was that the project was conceived as a response to a growing business problem. Time constraints have limited the scope of improvements to short-term, high-impact decisions that have high costs and have been implemented with minimal quantification of expected benefits.

The second problem was that the project was considered in isolation from the upstream value chain. Little attention has been paid to debottlenecking process interdependencies. After closing the initial productivity gap, tunnelers ran into a hurdle as subsequent processes struggled to keep up with the rate of penetration and the use of mechanized equipment dropped sharply.

The third problem, as shown by the subsequent audit, was that minimal process accuracy was used in this project. Decisions were made in isolation, with little stakeholder involvement, change management was not properly recorded or tracked, and costs were spread across several different items.

If there is one key lesson to be learned from the experience of this mine, it is that all performance improvements must be directly linked to securing and executing the mine plan.

"There's no point in running a 100m in 9 seconds if you're running in the wrong direction."

Seven times measure cut once

The truth is that productivity improvements can actually negatively affect the value of a project if approached in isolation, without thinking about the mining plan or the sustainability of the change. This is often seen when a company approaches productivity improvement through drastic cost reduction, prioritizing production and limiting footage. In the short term, this greatly improves performance. But once production fronts begin to dwindle, the result is often a production bottleneck and reduced productivity. Simply measuring performance is not enough.

"Not all performance is good performance."

To close the productivity gap, any company embarking on a productivity improvement project must be able to accurately quantify the long-term and short-term impact of its implementation on the mine plan. Once these implications are clear and you are ready to start implementing it, a reasonably rigorous methodology should be used to identify all relevant stakeholders, upstream and downstream process interdependencies, resource requirements, and expected benefits.

Progress tracking and reporting should be comprehensive without being burdensome. Reporting must reliably and accurately track performance improvement projects through various metrics and KPIs. For reporting, it is best to use those indicators that can be directly linked to the implementation of the mining plan.

In another real industry example, a mining company used monthly ore production (as opposed to a broader mining plan) as the main KPI for a contractor working at a mine. The contractor took on this indicator too zealously, supplementing the mining plan with the involvement of other available ore reserves in the extraction. The mine consistently outperformed production targets, and the contractor was compensated accordingly: he did what he was asked to do. However, the processing division of the enterprise provided information on discrepancies in the metal content and mineralogy of the ore. The contractor's initiatives had a tangible impact in the subsequent extraction process during processing, which affected the flow of profitability of the mine.

This example once again highlights the need for accurate performance measurements.

Subscribe for the latest news & events

Contact Details

Useful Links

News & Insights